Many out-of-province suppliers are trying to make inroads into the busy Saskatchewan mining and resource industries, and many are not finding much success. So, to create awareness of their company, they decide to (wait for it...) PLACE AN AD. Then, they try to figure out where they should place it. Then, they invest $400 or $1,500 or $5,000 and sit back to wait for the orders to roll in. And they sit. And sit. And sit. And wait. And nothing happens.

Many companies think about advertising as an event; something you do once - you PLACE AN AD. And, they've heard that you have to measure results, so if that one ad doesn't produce results, they come to the conclusion that advertising is a waste of money. And, when approached as an event, it largely IS a waste of money. Placing one ad is generally a waste, an expense. Not an investment.

Instead, we need to think about what we would do, not to create awareness, but to maintain awareness of our companies. To maintain awareness, we need repeated little touches with the people we want as customers. They need to see us in a magazine, read an article about us in the paper, see our name as a sponsor at their industry golf tournament, see us speak at a conference, and get the feeling that we're part of the fabric of their industry, and their community.

To maintain awareness, we need to think of advertising as a continual process, a series of touches, nudges and reminders. We need people to know that "We're here! Remember us when you need ..."

Don't waste your money on an advertisement to create awareness.

Do invest your money in a methodical campaign to maintain awareness.

Showing posts with label Standard Work. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Standard Work. Show all posts

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

Friday, March 25, 2011

Standardize to Reduce Effort

While some heavy-handed implementations of standards like ISO9001 can seem like a whole lot of extra effort for not much gain, standardizing the daily work can dramatically reduce your daily effort. By deciding in advance the best-known-method for handling a repetitive task, you reduce the time required to figure it out each time. A few simple examples...

- What do you do with a business card from a new contact? You can just pile them up and then, a few months later, try to figure out who all those people were. Or, you can have a simple, standard handling process that you always do with a new contact. If you have a CRM system that can automate this, or at least automate reminders for this, so much the better, but I've seen people handle this well with no technology other than a set of dated file folders. Perhaps you:

- Add it to your Address Book

- Send a "Nice to meet you email"

- Schedule a "Here's something you might find useful" contact in five weeks

- Make a "Hey, how you doing" phone call four weeks after that.

- Add them to your mailing list for periodic contact after that.

- How do you decide what kind of advertising and marketing to do? A marketing calendar, that standardizes your message and outlines what you will spend, when, on what, can dramatically reduce the effort required to get the word out. With a standard calendar, you then just need to make it happen, and don't have to waste your time and your mental energy on every opportunity that arises. And, if you measure which methods are producing results over time, you dramatically reduce the time and effort needed to create your marketing plan for the next year too. One small company decided on the following schedule, and successfully built their business for more than seven years with this simple plan:

- six magazine ads a year

- classifieds ads every week

- sponsor one industry golf tournament, and one industry curling bonspiel

- a public speaking engagement each quarter, shared among three business development people, and

- one networking event each month for each of the three business development people.

- What do you offer your customers? If you can do "anything for anybody", every sale requires starting from scratch. Can you bundle your offerings into a package? Can you calculate standard pricing in advance? Can you make it easier for your salespeople to tell customers what it is you do? Simple stuff, but these simple things can drive the costs and complexities of each transaction way down.

Labels:

Marketing,

Metrics,

Scheduling,

Standard Work,

Technology

Friday, January 7, 2011

When The Boss Isn't a Very Good Worker

The owner of a 30-person company would often pitch in, taking on some jobs within the organization to help out. With a desire to stay involved in the day-to-day operations, this owner would take on administrative and sales tasks, similar to what other employees in the organization had to do.

Unfortunately, the boss would hold himself to a different standard than employees doing the same job. So, if a reporting task needed to be done every day by 2 pm, employees would be expected to meet this goal. But the boss, doing the same task, would often miss the deadline "because he was busy on more important tasks," sometimes getting weeks behind on these daily activities. The resulting frustration and rippling consequences were having a significant effect on productivity and morale throughout the company.

As an owner, or manager, or team leader, or [insert other boss-like title here], if you take on some jobs to "help out," realize that you are no longer wearing your "boss" hat. When you pitch in to help out, you are wearing a "worker" hat, and need to hold yourself to the same standards as you would hold an employee doing the same job.

Sure, as an owner or manager or team lead, you need more freedom and flexibility in your day, and have more widely ranging responsibilities than your employees. But, if you take on the job of entering job status data by 2 p.m. every day, you bloody well better enter your job status data by 2 p.m. every day. If you can't do that reliably, fire yourself and hire someone that's more competent and reliable for the job.

Then, you can focus on leading, instead of mucking up the works by "helping out."

Unfortunately, the boss would hold himself to a different standard than employees doing the same job. So, if a reporting task needed to be done every day by 2 pm, employees would be expected to meet this goal. But the boss, doing the same task, would often miss the deadline "because he was busy on more important tasks," sometimes getting weeks behind on these daily activities. The resulting frustration and rippling consequences were having a significant effect on productivity and morale throughout the company.

As an owner, or manager, or team leader, or [insert other boss-like title here], if you take on some jobs to "help out," realize that you are no longer wearing your "boss" hat. When you pitch in to help out, you are wearing a "worker" hat, and need to hold yourself to the same standards as you would hold an employee doing the same job.

Sure, as an owner or manager or team lead, you need more freedom and flexibility in your day, and have more widely ranging responsibilities than your employees. But, if you take on the job of entering job status data by 2 p.m. every day, you bloody well better enter your job status data by 2 p.m. every day. If you can't do that reliably, fire yourself and hire someone that's more competent and reliable for the job.

Then, you can focus on leading, instead of mucking up the works by "helping out."

Labels:

Accountability,

Management,

Reliability,

Standard Work,

Teamwork,

Trust

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Is There Really a Top Priority?

How do you do time management in a real, messy company? In a real, messy management job?

Do you sort your tasks into A, B and C priorities, and then choose one of the A tasks and start hacking away at it? Then, when that one's done, you start hacking away at the next one. Or, more likely, you get interrupted by a crisis and get drawn back into the world of daily fire-fighting before you've made much progress on any top priority items.

One assumption that many people make is that they can somehow identify the top priority task, as if there is some universal rule that states "There will always be a single top priority." Unfortunately, that ain't the way it works.

It is very likely that there are two or four or five equally important areas you need to work on, four or five comparably-important tasks. The consequence of this is that you need a time management strategy that isn't based on finding the one top priority, but one that allows you to effectively make progress on several important priorities at the same time.

Think about it.

Do you sort your tasks into A, B and C priorities, and then choose one of the A tasks and start hacking away at it? Then, when that one's done, you start hacking away at the next one. Or, more likely, you get interrupted by a crisis and get drawn back into the world of daily fire-fighting before you've made much progress on any top priority items.

One assumption that many people make is that they can somehow identify the top priority task, as if there is some universal rule that states "There will always be a single top priority." Unfortunately, that ain't the way it works.

It is very likely that there are two or four or five equally important areas you need to work on, four or five comparably-important tasks. The consequence of this is that you need a time management strategy that isn't based on finding the one top priority, but one that allows you to effectively make progress on several important priorities at the same time.

Think about it.

Friday, November 19, 2010

Jumping Through Hoops

A small startup had a great product, a really creative team, and a number of small sales under their belts. Then, a BIG customer came along, one that would BREAK OPEN THE MARKET! The only problem was...

The BIG customer needed the startup to have a Quality Management System (ie. like ISO 9001-2008) to qualify as a supplier. The startup scrambled to find someone who could fix the problem in a hurry and get them an ISO registration. All they wanted to do was "jump through the hoop," to get the sale. "Our product is great; it's better and cheaper than the competition; what more do they want?"

The customer wants the product, true, but a sophisticated customer wants more than that. They want confidence in the supplier's records management and documentation control; they want established procedures and reilable and robust quality control; they want to know that you've designed your business, you've planned out your processes, and you work according to your plans. Sure they're just buying the product, but they have a strong interest in the reliability of your company as a whole too.

So, don't waste your time doing the minimum required to jump through a hoop. Embrace the requirement and make your company better, more capable, more reliable. Everybody wins.

The BIG customer needed the startup to have a Quality Management System (ie. like ISO 9001-2008) to qualify as a supplier. The startup scrambled to find someone who could fix the problem in a hurry and get them an ISO registration. All they wanted to do was "jump through the hoop," to get the sale. "Our product is great; it's better and cheaper than the competition; what more do they want?"

The customer wants the product, true, but a sophisticated customer wants more than that. They want confidence in the supplier's records management and documentation control; they want established procedures and reilable and robust quality control; they want to know that you've designed your business, you've planned out your processes, and you work according to your plans. Sure they're just buying the product, but they have a strong interest in the reliability of your company as a whole too.

So, don't waste your time doing the minimum required to jump through a hoop. Embrace the requirement and make your company better, more capable, more reliable. Everybody wins.

Wednesday, November 3, 2010

Boss Botches Bag, Nurse Nags Nicely

- Intravenous solution causes a red track up the patient's arm.

- IV disconnected, and replaced with new bag.

- Shift supervisor prepares a form to send to the lab to see if it's contaminated.

- Nurse says "I think we should send the name of the patient with it as well. The lab might have to talk to them, if they find something."

- Supervisor overrides her, saying "They don't need that."

- Not much later, the lab phones down and says they need the patient's name.

- The nurse informs the supervisor, and does very well not to say "I told you so".

Thursday, October 21, 2010

Home By Six

A manager in the Toronto office of a large insurance provider was having an odd problem with his staff. The overall corporate culture was one of long hours and competitive posturing between employees. If John started working until 6:15pm, Steve would one-up him and stay until 6:45pm. When Heather worked until 7:00pm, Janice would then stay even later. Soon, everyone was in the office until eight, nine at night.

A manager in the Toronto office of a large insurance provider was having an odd problem with his staff. The overall corporate culture was one of long hours and competitive posturing between employees. If John started working until 6:15pm, Steve would one-up him and stay until 6:45pm. When Heather worked until 7:00pm, Janice would then stay even later. Soon, everyone was in the office until eight, nine at night.In their daily work, none of their clients or insurance suppliers were working at these hours, and the manager was aware enough to realize that these long hours were not really about getting the work done. Gathering the staff together, the manager laid it on the line:

- You need to get your work done in the regular work day. If you can't, you need help with time management. We'll provide training and support. If that doesn't help, we need to examine our work flows and our capacity.

- If you don't want to go home at the end of the day, there's something wrong with your personal relationships and work-life balance. Our EAP provides free confidential counselling and coaching. Use it.

- "Home by Six" is now policy, and we'll help you achieve that, as part of our daily work.

We often talk of work-life balance, of respect for people, of the importance of family, of the need for rest and recuperation, yet how many of us live it? How many of us really encourage this for our staff?

You can demand more from your people than they can sustainably provide, and over time you will deplete them and have to replace them. This is a valid business model.

Or you can create a culture where life balance is truly valued, and still get the work done. If you are having retention problems, with high levels of stress and anxiety, perhaps something like "Home by Six" would work for you.

Monday, September 13, 2010

The Backbone of Your Organization

From one vertebrate to another, a backbone is a wonderful thing. Compared to slime molds, jelly fish and malpractice lawyers, our backbones give us integrity; holding us together and providing a unifying structure on which we can hang all our other nifty bits and pieces.

Working with companies to map and improve their work processes, it's clear that a good, solid process map can serve as a very effective organizational backbone.

First, you map out the things that you do, step-by-step-by-step, to do good things for your customers. Then, you examine every step of this step-by-step-by-step sequence of events. Then, you think about all the things that can and could and should and shouldn't happen at each step...

So, unless you work for Slime Mold Structures Inc., the Jelly Fish Facilitation Co., or the Wees Krew Yu & Laff Lawfirm, take a look a process mapping as a first step in understanding, controlling, and improving your business.

Working with companies to map and improve their work processes, it's clear that a good, solid process map can serve as a very effective organizational backbone.

First, you map out the things that you do, step-by-step-by-step, to do good things for your customers. Then, you examine every step of this step-by-step-by-step sequence of events. Then, you think about all the things that can and could and should and shouldn't happen at each step...

- Standard Work - Do the people involved in this step all do their work the best known way possible? How do you know? What typically prevents them from doing the work correctly? What gets in the way?

- Pride of Work - Do the people feel proud of this step? Do they enjoy their work? Is it mind-numbingly boring? Is it stimulating? What can you do to improve it?

- Customer Requirements - What are the requirements of the next step in the process? And the step after that? Do the workers know those requirements? Does the next step understand this step?

- Communication - What does this step communicate to the next? What do they fail to communicate? And vice versa?

- Training - Do the people know how to do this step? Is the training material correct? Is the work activity done correctly? What parts of this step are likely to be done wrong?

- Quality - Does this step produce stuff that meets specifications, that meets customer requirements? Are we following our stated work processes? Could we prove this to a customer? To a regulator?

- Regulations - Does this step conform to all applicable regulations? Some steps may have no regulations, some may have many? Do the people doing the work know what regulations are applicable?

- Standards - Are we following the applicable standards in this step, both internal and external? What could cause a non-conformance at this step?

- Capacity - How much can this step produce? How much does it need to produce? Is it a bottleneck? Is it consistent?

- Variation - What causes results to vary at this step? How much variation is there? Is this part of the system in control or does it fluctuate wildly due to special causes?

- Safety - How can a person hurt themselves in this step? What opportunities for injury can we address? What are the ergonomics of this step? How can we improve them?

- Errors - What kind of errors could happen here? What are the consequences of an error here? Does this step produce a lot of rework? Can we disrupt the possibility of an error here?

- Ethics - Do our people face ethical dilemna's in this step? Privacy issues? Inappropriate temptations? Couldn't we anticipate these and address them in advance?

- Waste - Does this step add value for our customers? Is this waiting or transportation really necessary? Are we producing more than the next step can handle? Does all that frenzied motion really make our service better? Can't we identify these wastes and get rid of them? Can't we make our backbone stronger?

- Risk - Does this step expose the organization to risks, whether liability, injury, financial, security, technical, intellectual property, or maybe even a really big explosion?

- Reporting - What do we truly need to know about this step to manage our company? What do we measure? What should we measure?

- Money - What are the costs and investments associated with this step? Can they be identified? Verified? What about contributions to revenue? What about added value? What about efficient use of resources?

So, unless you work for Slime Mold Structures Inc., the Jelly Fish Facilitation Co., or the Wees Krew Yu & Laff Lawfirm, take a look a process mapping as a first step in understanding, controlling, and improving your business.

Wednesday, September 8, 2010

A Little Over-Processing Waste at the Pharmacy

A pharmacy has a software system that prints three items at once - a label for the bottle, a receipt for the customer, and a record slip for the files. The software system is robust and reliable.

As part of their work process, one pharmacist routinely checks the information on all three items to make sure it is the same. This is not to make sure that it is correct, this is to make sure that the three pieces are the same. This cursory check takes about 20 seconds and is done on the basis that "you can never be too careful."

Truth be told, you can be too careful, if you're being careful in a way that doesn't actually help anything. These printed pieces are never different; they will never be different; the inspection will never find a problem. The inspection is a hold-over from experiences with previous systems that weren't robust; with the current system, the inspection is not needed.

In Lean terminology, this extra effort, this double check, this inspection, is Waste, specifically Over-Processing waste. It is a step that takes time and effort, but doesn't add any value for the customer.

And these wastes, tiny as they seem, really add up. Consider that 20 seconds/prescription x 200 prescriptions/day x 250 days/year = 275 hours wasted each year. Eliminating this step from the process could free up 275 hours for a pharmacist every year! That's almost two months! Finding and eliminatng a few more small wastes could potentially free up the equivalent of a full-time pharmacist, without adding any new staff.

That's the excitement of Lean and the potential of continuous daily improvement.

As part of their work process, one pharmacist routinely checks the information on all three items to make sure it is the same. This is not to make sure that it is correct, this is to make sure that the three pieces are the same. This cursory check takes about 20 seconds and is done on the basis that "you can never be too careful."

Truth be told, you can be too careful, if you're being careful in a way that doesn't actually help anything. These printed pieces are never different; they will never be different; the inspection will never find a problem. The inspection is a hold-over from experiences with previous systems that weren't robust; with the current system, the inspection is not needed.

In Lean terminology, this extra effort, this double check, this inspection, is Waste, specifically Over-Processing waste. It is a step that takes time and effort, but doesn't add any value for the customer.

And these wastes, tiny as they seem, really add up. Consider that 20 seconds/prescription x 200 prescriptions/day x 250 days/year = 275 hours wasted each year. Eliminating this step from the process could free up 275 hours for a pharmacist every year! That's almost two months! Finding and eliminatng a few more small wastes could potentially free up the equivalent of a full-time pharmacist, without adding any new staff.

That's the excitement of Lean and the potential of continuous daily improvement.

Labels:

Continuous Improvement,

Health Care,

Lean,

Service,

Standard Work

Friday, August 27, 2010

Could You Duplicate Your Organization?

So, you're chugging along with your successful little organization, whether a five-person beauty salon, a call center with fifty service reps, or a hospital ward with 250 staff. You're managing. They're working. Things are getting done. It's a little chaotic, but then that's how business is, isn't it?

Then, for some reason, you're called upon to duplicate your results - to spread the gospel of what you do and how you do it. How easy would it be for you to open another salon, build a sister call center in another city, or repeat your ward's success in twenty other Health Regions? Could you start tomorrow?

All organizations, and all managers, can benefit from this thought exercise: Could you duplicate your organization tomorrow based on what you have in place today?

How do you know what to do and how to do it? How do your people know what to do and how to do it? Do you know, start-to-finish, how your processes work? Do your people have standard work defined, with clearly defined work methods and sequence? Do they actually follow it? Do they value it? Do your standard work processed continually improve as you collectively discover even better methods to do what you do?

Look at your workplace as if you wanted to create a chain of franchises tomorrow - could you communicate all the important details of how you do what you do? Think about it.

Then, for some reason, you're called upon to duplicate your results - to spread the gospel of what you do and how you do it. How easy would it be for you to open another salon, build a sister call center in another city, or repeat your ward's success in twenty other Health Regions? Could you start tomorrow?

All organizations, and all managers, can benefit from this thought exercise: Could you duplicate your organization tomorrow based on what you have in place today?

How do you know what to do and how to do it? How do your people know what to do and how to do it? Do you know, start-to-finish, how your processes work? Do your people have standard work defined, with clearly defined work methods and sequence? Do they actually follow it? Do they value it? Do your standard work processed continually improve as you collectively discover even better methods to do what you do?

Look at your workplace as if you wanted to create a chain of franchises tomorrow - could you communicate all the important details of how you do what you do? Think about it.

Monday, August 9, 2010

Attack, Indulge or Ignore?

When you're trying to improve, and you don't meet your own expectations, how do you handle it? What does the little voice say when you fall short?

Do you attack? Does the voice say things like "You sure screwed up. You're lazy. What's wrong with you? Why can't you follow through on your goals? You need to be more self-disciplined."

Do you indulge? Do you comfort yourself with "You deserve a break; don't be so hard on yourself. Look at all the other things you've accomplished. What's the big deal if you let this slide? Have another chocolate, you worked hard!"

Do you ignore? Does the voice stay silent, trying to pretend that you never really had a goal in the first place? Trying to pretend that you didn't give up when the going got tough? Maybe next time something will inexplicably change and you will magically be able to meet your goals.

These are the three common ways we talk to ourselves when we don't measure up to our expectations, says Pema Chodron in Comfortable with Uncertainty: 108 Teachings on Cultivating Fearlessness and Compassion (Shambhala Library) . These are also the three common ways we managers deal with shortcomings in our employees and teams.

. These are also the three common ways we managers deal with shortcomings in our employees and teams.

We attack them, and use our HPS (Hierarchical Power Stick) to whack them until they're motivated.

We indulge them, channelling our inner-jellyfish to give them the benefit of the doubt, hold a love-fest, a pity-fest, and dream up excuses that might explain why they couldn't meet the challenge.

Or, we ignore them, pretending that we never actually started that initiative. We forget our original intent to improve, and watch quietly as things slide back to the way they were.

Chodron suggests a fourth option for dealing with personal shortcomings, that of openly experiencing the failure, embracing the failure, being aware of but accepting of the failure. When we allow ourselves to truly delve into the failure and really see it, we can learn. We can gain insight about what we might do differently to achieve more graceful success in the future.

When you experience a really good Root Cause Analysis process in an open and collaborative environment, you get a corporate-feel for what Chodron is talking about on a personal level. When you practice effective standard work, striving to always figure out what is keeping you and your people from getting your daily tasks done, you see the same benefits.

Next time you or your team falls short of your improvement expectations, observe whether you tend to attack, indulge or ignore. Then, consider how your improvement process might itself be improved by encouraging your whole team to openly experience the failure together and discover better ways to do what you do.

Do you attack? Does the voice say things like "You sure screwed up. You're lazy. What's wrong with you? Why can't you follow through on your goals? You need to be more self-disciplined."

Do you indulge? Do you comfort yourself with "You deserve a break; don't be so hard on yourself. Look at all the other things you've accomplished. What's the big deal if you let this slide? Have another chocolate, you worked hard!"

Do you ignore? Does the voice stay silent, trying to pretend that you never really had a goal in the first place? Trying to pretend that you didn't give up when the going got tough? Maybe next time something will inexplicably change and you will magically be able to meet your goals.

These are the three common ways we talk to ourselves when we don't measure up to our expectations, says Pema Chodron in Comfortable with Uncertainty: 108 Teachings on Cultivating Fearlessness and Compassion (Shambhala Library)

We attack them, and use our HPS (Hierarchical Power Stick) to whack them until they're motivated.

We indulge them, channelling our inner-jellyfish to give them the benefit of the doubt, hold a love-fest, a pity-fest, and dream up excuses that might explain why they couldn't meet the challenge.

Or, we ignore them, pretending that we never actually started that initiative. We forget our original intent to improve, and watch quietly as things slide back to the way they were.

Chodron suggests a fourth option for dealing with personal shortcomings, that of openly experiencing the failure, embracing the failure, being aware of but accepting of the failure. When we allow ourselves to truly delve into the failure and really see it, we can learn. We can gain insight about what we might do differently to achieve more graceful success in the future.

When you experience a really good Root Cause Analysis process in an open and collaborative environment, you get a corporate-feel for what Chodron is talking about on a personal level. When you practice effective standard work, striving to always figure out what is keeping you and your people from getting your daily tasks done, you see the same benefits.

Next time you or your team falls short of your improvement expectations, observe whether you tend to attack, indulge or ignore. Then, consider how your improvement process might itself be improved by encouraging your whole team to openly experience the failure together and discover better ways to do what you do.

Monday, July 5, 2010

I See You Shiver, With Antici...pation

You're faced with a choice between some sizzling bacon and some raw brocolli . Do you choose the brocolli with its anti-oxidants and nutritional goodness, or do you choose the bacon, with its mouth-wateringly delicious fatty yummy-ness? You won't really know the health impact for years, and even then you won't be sure what effect this choice really had on your long term health.

The immediate feedback is about flavour and pleasure, and the bacon wins easily (be honest!). The long-term feedback is about health, but this has little effect on our immediate motivation. When we expect to receive feedback on our choices has a big effect on the kind of choices we make.

In the workplace, it turns out that when we expect to get feedback also has a big effect on how well we perform. Keri Kettle at the University of Alberta School of Business published some interesting findings in his paper Motivation by Anticipation: Expecting Rapid Feedback Enhances Performance. University students performed objectively better (22% better) when they anticipated immediate feedback on their speaking presentations, compared to when they were told to expect feedback in a couple of weeks. The effect was strong and linear, meaning that an anticipated delay of eight days for feedback reduced performance by about twice as much as an expected delay of four days.

This suggests that our traditional best-practices in performance management are crap ... or, to be polite, marginally effective. The annual performance review is so far in the future that it provides little motivation and no feedback day-to-day. Moving to quarterly performance reviews is little better (remember that a two-week delay in Kettle's study resulted in twenty percent poorer performance). So, annual and quarterly performance reviews are useless, monthly reviews are still weak, and weekly performance reviews not much better, but this starts getting ridiculous - we can't have daily performance reviews, can we? That's crazy talk!

In the traditional world of performance management, daily performance reviews would be crazy. But we can find effective ways to provide immediate feedback, and leverage this principle of Motivation by Anticipation to improve our desire to perform well and avoid dissappoinment.

Consider the daily, tiered accountability meetings of Leader Standard Work from the world of Lean, or the daily Scrum meetings from the world of Agile Software Development. When done well, these approaches shift the feedback towards short, structured meetings about immediate daily progress. Visual displays of status also constribute to making progress understandable at a glance. In Lean, the feedback time frame is further shortened to match the takt time, the heartbeat of the process, which may be as short as a few minutes depending on the facility. Imagine getting non-judgemental feedback about your performance every few minutes. This aligns perfectly with Kettle's work, and suggests why working in a well-run Lean or Agile organization can be such a pleasure, and produce such good results.

When we choose bacon over brocolli, we're choosing immediate feedback over future feedback. If there were a way to make feedback on the health benefits immediately concrete and real, we would likely choose the healthy alternative more often, and our personal health performance would improve dramatically.

Kettle shows that expecting rapid feedback enhances performance. If our corporate Performance Management efforts are truly intended to improve performance, we need to shift away from the disconnected, long-term evaluation inherent in our current review processes. We need to shift towards providing immediate, concrete feedback - daily, hourly. We need to foster an expectation of immediate, concrete feedback amongst our people. And this means that management needs to change. Management needs to do standard daily work. Immediate feedback one day and no feedback the next is not enough. Management needs to step up its consistency.

By building the expectation of rapid feedback, we can get better performance, better intrinsic motivation, and better results. It's like getting the health benefits of broccoli with the flavor goodness of bacon. Yum.

The immediate feedback is about flavour and pleasure, and the bacon wins easily (be honest!). The long-term feedback is about health, but this has little effect on our immediate motivation. When we expect to receive feedback on our choices has a big effect on the kind of choices we make.

In the workplace, it turns out that when we expect to get feedback also has a big effect on how well we perform. Keri Kettle at the University of Alberta School of Business published some interesting findings in his paper Motivation by Anticipation: Expecting Rapid Feedback Enhances Performance. University students performed objectively better (22% better) when they anticipated immediate feedback on their speaking presentations, compared to when they were told to expect feedback in a couple of weeks. The effect was strong and linear, meaning that an anticipated delay of eight days for feedback reduced performance by about twice as much as an expected delay of four days.

This suggests that our traditional best-practices in performance management are crap ... or, to be polite, marginally effective. The annual performance review is so far in the future that it provides little motivation and no feedback day-to-day. Moving to quarterly performance reviews is little better (remember that a two-week delay in Kettle's study resulted in twenty percent poorer performance). So, annual and quarterly performance reviews are useless, monthly reviews are still weak, and weekly performance reviews not much better, but this starts getting ridiculous - we can't have daily performance reviews, can we? That's crazy talk!

In the traditional world of performance management, daily performance reviews would be crazy. But we can find effective ways to provide immediate feedback, and leverage this principle of Motivation by Anticipation to improve our desire to perform well and avoid dissappoinment.

Consider the daily, tiered accountability meetings of Leader Standard Work from the world of Lean, or the daily Scrum meetings from the world of Agile Software Development. When done well, these approaches shift the feedback towards short, structured meetings about immediate daily progress. Visual displays of status also constribute to making progress understandable at a glance. In Lean, the feedback time frame is further shortened to match the takt time, the heartbeat of the process, which may be as short as a few minutes depending on the facility. Imagine getting non-judgemental feedback about your performance every few minutes. This aligns perfectly with Kettle's work, and suggests why working in a well-run Lean or Agile organization can be such a pleasure, and produce such good results.

When we choose bacon over brocolli, we're choosing immediate feedback over future feedback. If there were a way to make feedback on the health benefits immediately concrete and real, we would likely choose the healthy alternative more often, and our personal health performance would improve dramatically.

Kettle shows that expecting rapid feedback enhances performance. If our corporate Performance Management efforts are truly intended to improve performance, we need to shift away from the disconnected, long-term evaluation inherent in our current review processes. We need to shift towards providing immediate, concrete feedback - daily, hourly. We need to foster an expectation of immediate, concrete feedback amongst our people. And this means that management needs to change. Management needs to do standard daily work. Immediate feedback one day and no feedback the next is not enough. Management needs to step up its consistency.

By building the expectation of rapid feedback, we can get better performance, better intrinsic motivation, and better results. It's like getting the health benefits of broccoli with the flavor goodness of bacon. Yum.

Labels:

Accountability,

Lean,

Performance Management,

Standard Work

Thursday, June 24, 2010

GET Organized, or STAY Organized

One owner/manager lamented that she just needed to "get organized" and went on to describe all the previous attempts she'd made to add some calmness and order to her chaotic business place. As she rattled off the various attempts to get control of paper work, inventory, procedures, staffing, invoicing, and storage, a familiar pattern formed. All of the attempts were "events", ranging from a weekend all-staff clean-up bee in the back room, to a two-day focused effort to get the backlog of paperwork filed away.

The repeated hope was that after this event, they'd be organized. After this event, they'd somehow magically be inspired to stay on top of it; they'd magically become disciplined enough to keep it organized. Of course, the discipline was the hard part and nothing ever changed for the better.

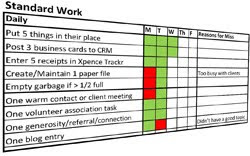

Rather than trying to get organized, an interesting and effective alternative is to set yourself up to stay organized. When you think of the behaviours you'd do to stay organized, you'll see that they're not big events, they're little actions, done in predictable, standard ways.

To stay organized, you put things in their standard places. To stay organized, you do tasks in the same standard way. You clean up after yourself. You do the small things the same way each time, every hour, every day. In Project Management vocabulary, this is the Work Breakdown Structure, chopping up big daunting tasks into small, achievable, reportable steps.

To stay organized, you put things in their standard places. To stay organized, you do tasks in the same standard way. You clean up after yourself. You do the small things the same way each time, every hour, every day. In Project Management vocabulary, this is the Work Breakdown Structure, chopping up big daunting tasks into small, achievable, reportable steps.

You'll quickly make progress on the big projects, without ever doing a big project. And you'll have developed easy standard work habits that help you stay organized, which is way more satisfying and valuable than just getting organized.

The repeated hope was that after this event, they'd be organized. After this event, they'd somehow magically be inspired to stay on top of it; they'd magically become disciplined enough to keep it organized. Of course, the discipline was the hard part and nothing ever changed for the better.

Rather than trying to get organized, an interesting and effective alternative is to set yourself up to stay organized. When you think of the behaviours you'd do to stay organized, you'll see that they're not big events, they're little actions, done in predictable, standard ways.

To stay organized, you put things in their standard places. To stay organized, you do tasks in the same standard way. You clean up after yourself. You do the small things the same way each time, every hour, every day. In Project Management vocabulary, this is the Work Breakdown Structure, chopping up big daunting tasks into small, achievable, reportable steps.

To stay organized, you put things in their standard places. To stay organized, you do tasks in the same standard way. You clean up after yourself. You do the small things the same way each time, every hour, every day. In Project Management vocabulary, this is the Work Breakdown Structure, chopping up big daunting tasks into small, achievable, reportable steps.So, as a start on the road to staying organized, don't rely on a To Do List or Checklist of big events, big projects you need to do. Instead, create a very small list of very small actions you will do every day that will lead you in the direction you want to go; a visual list of manageable daily standard work.

- Instead of "File all the old invoices", try "File one old invoice", every day.

- Instead of "Clean out the chemical storage area", try "Discard one outdated chemical", every day.

- Instead of "Create a tool storage system", try "Put two things in their place", every day.

- Instead of "Contact people I met at trade show", try "Phone one contact from the trade show", every day.

- Instead of "Write a book", try "Write one blog entry under 300 words", every day.

Make this list visual (Green and Red!). Post it somewhere. Ask an accountability partner to review it with you daily and help you address things that prevented you from completing "missed" activities.

You'll quickly make progress on the big projects, without ever doing a big project. And you'll have developed easy standard work habits that help you stay organized, which is way more satisfying and valuable than just getting organized.

Labels:

Change,

Project Management,

Scheduling,

Standard Work

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

Change Won't Stick Without Changing What Managers Do

We add some new shelving to help get organized. We move several workstations together to improve flow. We create a place for everything, with everything in its place. We change a procedure; write a new policy. We change something, anything, about the nature of the work, and we'd like the change to stick. But it doesn't.

So we set up training courses, write thick manuals, post signs to remind people, create an intranet, and send out memos. We plead for discipline, for attention to detail, for people to do what they're supposed to do, but within a very short time, the new shelving is disorganized, flow has stopped, everything is not in its place, and the signs, procedures and memos go unread, and unused.

So we set up training courses, write thick manuals, post signs to remind people, create an intranet, and send out memos. We plead for discipline, for attention to detail, for people to do what they're supposed to do, but within a very short time, the new shelving is disorganized, flow has stopped, everything is not in its place, and the signs, procedures and memos go unread, and unused.

So, when we organize a shelf, it's not enough to stop there. We might go farther and ask questions like - Who will keep the shelf organized? How can we tell at a glance that the shelf is properly organized? How do we know what is supposed to be on the shelf, and what is not supposed to be on the shelf? How do we know what to do when something is missing? How often should the shelf be checked? What do we do when we get new stuff for the shelf?

So, when we organize a shelf, it's not enough to stop there. We might go farther and ask questions like - Who will keep the shelf organized? How can we tell at a glance that the shelf is properly organized? How do we know what is supposed to be on the shelf, and what is not supposed to be on the shelf? How do we know what to do when something is missing? How often should the shelf be checked? What do we do when we get new stuff for the shelf?

So, we answer these valid questions, and use them to set up some standard work for Paul, the new Shelf Organizing Guy. But Paul gets busy, Paul gets pulled onto other important tasks, and no one asks Paul about the shelf until three weeks later when something that's supposed to be there is not. Then we have a crisis, with finger pointing, blame, and misguided accountability - "Paul was responsible for this - why didn't he do his job?"

Instead of this dysfunctional and ineffective change strategy, management needs to become part of the daily accountability process. Paul's team leader Steve needs to change some of his own standard work to support the change and help it stick. Steve's standard work might include a daily check of Paul's standard work list, a periodic spot check of the shelf itself, and immediate support to resolve problems that have prevented Paul from doing his standard work. And the facility manager's standard work might include a daily check of Steve's standard work, and immediate support to resolve problems that have prevented Steve from helping Paul. Eventually, maintaining the new shelf becomes a part of "how we do things around here", but that change is not an event, it's a process.

If any of this sounds like effort, it is. Remember that everything is impermanent, everything requires maintenance, and maintenance requires effort. But the minimal daily effort of standard work is nothing compared to the chaos and frustration of the alternative. The next time you plan an improvement, don't just plan a change event. Plan how management's daily standard work will change to support the improvement. That's how to make it stick.

So we set up training courses, write thick manuals, post signs to remind people, create an intranet, and send out memos. We plead for discipline, for attention to detail, for people to do what they're supposed to do, but within a very short time, the new shelving is disorganized, flow has stopped, everything is not in its place, and the signs, procedures and memos go unread, and unused.

So we set up training courses, write thick manuals, post signs to remind people, create an intranet, and send out memos. We plead for discipline, for attention to detail, for people to do what they're supposed to do, but within a very short time, the new shelving is disorganized, flow has stopped, everything is not in its place, and the signs, procedures and memos go unread, and unused.When we set out to make an improvement, we usually think of a specific change, of an event, of something to cross off our list. "Organize the storage area ... check. Change the warranty claim procedure ... check." We like to accomplish things and it's comforting to believe that we've improved things, we're done, things will be better now. But that's not the way it works.

Everything we create is impermanent. Nothing stays the way we'd like it. Everything changes, deteriorates, requires maintenance. We hate to acknowledge this, because it's uncomfortable, but it's a truth that permeates both philosophical writings like Pema Chodron's Comfortable with Uncertainty and practical business guides like David Mann's Creating a Lean Culture

and practical business guides like David Mann's Creating a Lean Culture .

.

For every change we want to make, we need to look beyond the change itself, and look to how we will sustain it; how we will make it a part of "how we do things around here". In the workplace, each technical or structural change also requires complementary changes in what management does, not just in what the workers do. This piece is almost always ignored when we change the design of our work - the leader thinks "This is a change for the workers, not for me," and soon everything reverts back to the way it was before.

Most leaders do not understand or embrace the concept of Standard Work, of having some specific clearly-defined tasks that leaders need to do each day, or even each hour. "That's for front line staff, not me." Yet what the leaders do - what the leaders care about, ask about, talk about - directly affects what everyone else does. What the leader shows to be important, is what actually is important.

So, when we organize a shelf, it's not enough to stop there. We might go farther and ask questions like - Who will keep the shelf organized? How can we tell at a glance that the shelf is properly organized? How do we know what is supposed to be on the shelf, and what is not supposed to be on the shelf? How do we know what to do when something is missing? How often should the shelf be checked? What do we do when we get new stuff for the shelf?

So, when we organize a shelf, it's not enough to stop there. We might go farther and ask questions like - Who will keep the shelf organized? How can we tell at a glance that the shelf is properly organized? How do we know what is supposed to be on the shelf, and what is not supposed to be on the shelf? How do we know what to do when something is missing? How often should the shelf be checked? What do we do when we get new stuff for the shelf?So, we answer these valid questions, and use them to set up some standard work for Paul, the new Shelf Organizing Guy. But Paul gets busy, Paul gets pulled onto other important tasks, and no one asks Paul about the shelf until three weeks later when something that's supposed to be there is not. Then we have a crisis, with finger pointing, blame, and misguided accountability - "Paul was responsible for this - why didn't he do his job?"

Instead of this dysfunctional and ineffective change strategy, management needs to become part of the daily accountability process. Paul's team leader Steve needs to change some of his own standard work to support the change and help it stick. Steve's standard work might include a daily check of Paul's standard work list, a periodic spot check of the shelf itself, and immediate support to resolve problems that have prevented Paul from doing his standard work. And the facility manager's standard work might include a daily check of Steve's standard work, and immediate support to resolve problems that have prevented Steve from helping Paul. Eventually, maintaining the new shelf becomes a part of "how we do things around here", but that change is not an event, it's a process.

If any of this sounds like effort, it is. Remember that everything is impermanent, everything requires maintenance, and maintenance requires effort. But the minimal daily effort of standard work is nothing compared to the chaos and frustration of the alternative. The next time you plan an improvement, don't just plan a change event. Plan how management's daily standard work will change to support the improvement. That's how to make it stick.

Labels:

Accountability,

Change,

Lean,

Management,

Standard Work

Tuesday, June 15, 2010

When Things Get Busy

A disorganized but successful salesman wanted to restore order to his cluttered office and get control of his business. On Tuesday, he made a checklist of specific cleanup tasks he'd do every day to address the problems. He planned to enter three business cards from the overflowing pile into his mailing list program, clean out and review one paper customer file, file five old invoices, and contact one past customer for followup. On the first two days, he got through all the items on the list, and was very excited about the potential improvements - maybe this time he'd be able to truly clean up his chaotic messes!

On Thursday, he got a call that made him suddenly very busy and also made it very, very tempting to give up on the new standard work. The call was for some new business that would start the next day, business that he hadn't done before and that would need some significant preparation time. So he faced a decision.

Should he prepare for the new business, and skip the new improvement tasks? Or, should he stick to his checklist, do the improvement tasks, and risk being unprepared for the new business? Or, should he work furiously and try to do it all?

So often, we start a new initiative with high hopes, with dreams for a better world, with dreams for a cleaner office! Then, when we've barely gotten started, we get busy with some new crisis or opportunity and we're faced with this kind of a decision.

What happens to your "I'm-going-to-do-these-every-day" tasks when things get busy? Take a look at the Lean methods of Leader Standard Work if this kind of thing routinely happens in your business.

On Thursday, he got a call that made him suddenly very busy and also made it very, very tempting to give up on the new standard work. The call was for some new business that would start the next day, business that he hadn't done before and that would need some significant preparation time. So he faced a decision.

Should he prepare for the new business, and skip the new improvement tasks? Or, should he stick to his checklist, do the improvement tasks, and risk being unprepared for the new business? Or, should he work furiously and try to do it all?

So often, we start a new initiative with high hopes, with dreams for a better world, with dreams for a cleaner office! Then, when we've barely gotten started, we get busy with some new crisis or opportunity and we're faced with this kind of a decision.

What happens to your "I'm-going-to-do-these-every-day" tasks when things get busy? Take a look at the Lean methods of Leader Standard Work if this kind of thing routinely happens in your business.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)